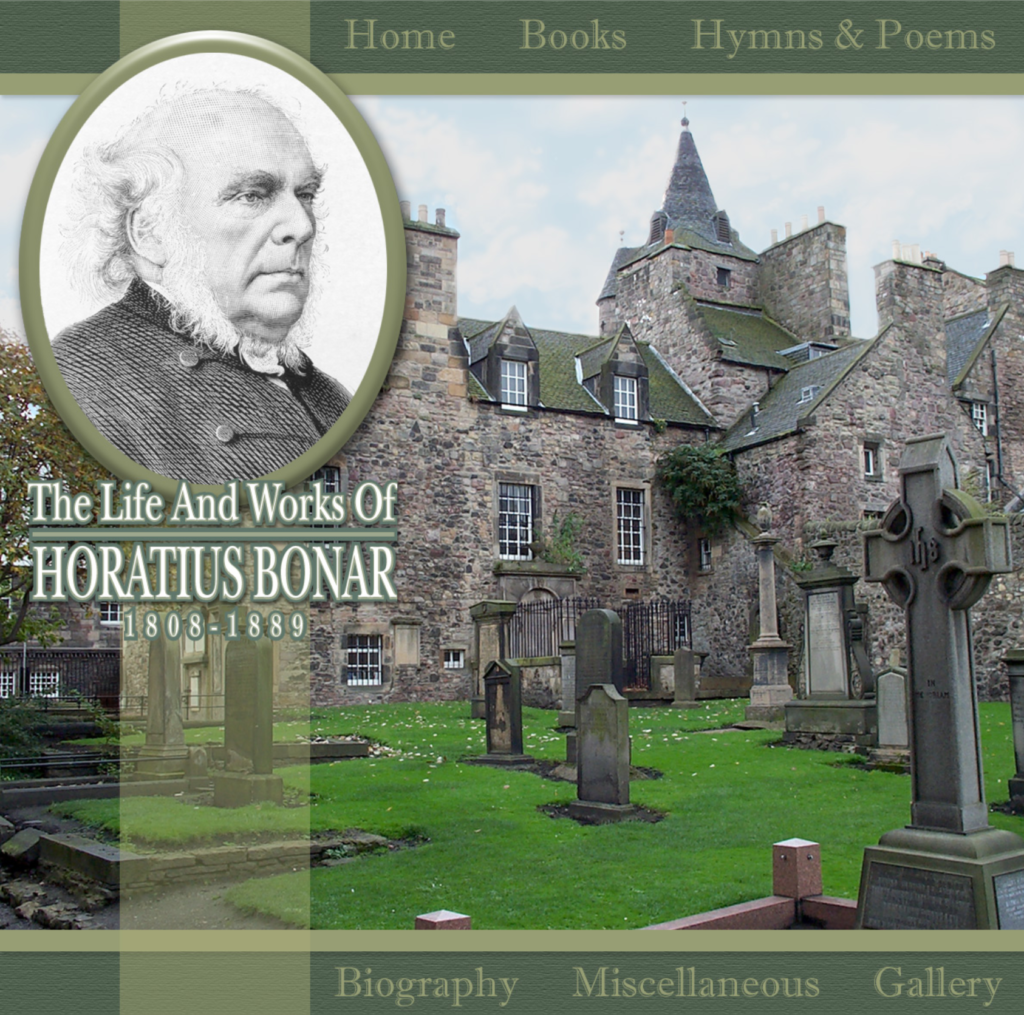

In 2004 I completed a three year project compiling the works of the Scottish Presbyterian minister, Horatius Bonar. It was a general admiration for the humble life of a man that led me to complete the 13,000 page project and release it in PDF format; along with the fact that it had not been done before. Below is the short biography I wrote to accompany the work.

Before his death on July 31st, 1889, Rev. Horatius Bonar asked that no memoir of his life be written. Unfortunately for later generations, this request was honoured by those who knew and revered Dr. Bonar, and now little is known about the man apart from that which can be garnered from small biographical sketches and the personal recollections of friends. Despite authoring three biographies of eminent ministers in his own day, Bonar did not want the story of his life and ministry to in any way obscure the glory of Jesus Christ; to whom he hoped his life would point. He was a man who toiled ceaselessly to warn sinners of impending judgment and one whom God used greatly in 19th century Scotland for the saving of souls.

Horatius Bonar was born in Edinburgh on December 19th, 1808. He was one of seven boys, three of which entered upon gospel ministry (John James, Horatius, and Andrew) in their early years. He was ordained a minister in the Church of Scotland on November 30th, 1837, and was later given charge over the North Parish Church in Kelso. Bonar was counted among the dissenting ministers who left the Established Church to form the Free Church of Scotland in what was known as the Disruption of 1843. In 1866 he accepted a call to pastor in Edinburgh at the newly erected Chalmers Memorial Church. He was one in a long line of ministers in the Bonar family. In the May 1908 edition of The Scotsman magazine, they estimated that the Bonar descendants (John Bonar 1671-1747) served a total of 364 years in the pulpits of Scottish churches.

From the pulpit, Bonar’s message was simple and clear: he preached a crucified and risen Christ, whose righteousness alone was the only hope of sinners. He was adept in the exposition of a free gospel through the necessary sovereign workings of the Holy Spirit. His presentation always placed an emphasis on the urgent and immediate necessity of leaving one’s sin and coming to Christ; and this as the only means of reconciliation between man and God. In a rare autobiographical piece, Dr. Bonar wrote of his theology:

“Righteousness without works to the sinner, simply on his acceptance of the Divine message concerning Jesus and His sufficiency,—this has been the burden of our good news…It is one message, one gospel, one cross, one sacrifice, from which nothing can be taken and to which nothing can be added. This is the…beginning and the ending of our ministry.”

Dr. Bonar’s preaching was thoroughly biblical. He added nothing superfluous or superficial. He was not blessed with commanding powers of oration, but rather, was characterized as a sober and erudite preacher. It was once asked of one of his congregants if he was an eloquent man to which was replied, “No, he was not eloquent, but his doctrine was full and clear.” It was not his presence in the pulpit that captivated, for there was nothing in Dr. Bonar’s exposition that aimed at merely affecting the emotions. It was in his powerful and effective presentation of the evil of sin and the approaching doom of the impenitent sinner combined with an earnest commendation of Christ that moved his hearers. He strove to preach a biblical gospel that proclaimed the glory of God in the fullness of Christ; not one ashamedly suited for ‘itching ears’. Commenting on the state of the Christian faith in his day, Bonar once wrote: “It is not opinions that man needs, it is TRUTH. It is not theology, it is GOD. It is not religion, it is CHRIST. It is the knowledge of the free love of God in the gift of His only-begotten Son;” and it was towards these ‘needs’ that Bonar aimed his message.

Dr. Bonar had a modest estimate of his abilities, coupled with a seemingly boundless capacity for work. He edited and contributed to various magazines and periodicals; he wrote books, tracts, and hymns. His pen was scarcely idle. Whether it was a word of comfort to the afflicted saint or sound encouragement for the mature believer, his books were written with the sole purpose of communicating the truths of Scripture to the hearts and minds of his readers. Lord Polwarth, when asked to pay tribute to the writings of Dr. Bonar, remarked,

“…when I think of Dr. Bonar…as a writer, it is like a pure, broad light shining from heaven, where all the promises of salvation to men on earth appear to pour down as the perfect divine revelation, with nothing of man’s embellishment…it is all the divine message from beginning to end. Study the poetry, study the prose, you will feel the heart of God beating through it all.”

While the subject matter often varied, it almost always led the reader back to the central message of Scripture: the person and work of Christ. Christ was the sum and substance of every sermon Bonar preached, and every hymn or book he wrote to instruct and teach the dear saints of God. Two of his most notable works were God’s Way of Peace, and its companion volume, God’s Way of Holiness. In these books, Bonar outlined the doctrines of justification and sanctification and showed the profound importance that each of these play in the life of the Christian. He was also one of the foremost advocates of “pre-millennarian” eschatology and wrote extensively on this subject. He edited The Quarterly Journal of Prophecy for twenty-five years and summarized his eschatological views in a book entitled Prophetical Landmarks. The second advent of Christ was a doctrine that engaged much of Bonar’s efforts as he believed it had been “the hope of the Church through many a starless night when other hopes had gone out one by one…leaving her disconsolate and helpless.” Dr. Bonar strongly held that the knowledge and hope of Christ’s imminent return could dispel the darkness and afford a blessed comfort to the Christian.

The Reverend Bonar’s ministry extended beyond both the pulpit and the pen as he was known to spend countless hours in the spiritual care of the children in his parish. He considered it one of the minister’s foremost responsibilities to instruct and teach the little ones in the ways of the gospel. A young girl recalls her experience in a Bible class conducted by her minister:

“I sometimes wonder if any one else ever possessed the faculty that he had of drawing towards him the affection of young people, which, when you were once brought under the charm of his friendship, could never afterwards be lost or lessened. How well I remember his class for us girls! We would not for all the world have missed that hour on Wednesday afternoon. I think I see the little room…where we gathered, a bright, happy band of school- girls, sitting around to listen to his earnest, loving, faithful teaching. I see Dr. Bonar seated at the end of the long table with the large Bible spread out before him, the Bible hymn book in his hand, his dear handsome face beaming, and the pleasant smile which lighted it up, as some of us gave a fuller, clearer answer than he expected to the question asked. And then the last meeting before the holidays; what a solemn hour it was, as he reminded us that never again here below should we all meet together, and spoke of the meeting-place above. All kneeling down, to be each tenderly commended to the loving care of our heavenly Father, bathed in tears, we could hardly tear ourselves away, lingering long after the usual time.”

It was this affectionate love and concern for the spiritual welfare of these little ones that led him to the writing of hymns. The children he was ministering to had difficulty in understanding the metrical Psalms used in the Presbyterian Church, so he began to write hymns for them that could be sung in their Sabbath school. He set his hymns to simplistic tunes and the children loved them. Dr. Bonar viewed his hymns as a means of both enriching the mind and stirring the affections in the worship of God. He understood the power of music and how that power could be harnessed to effectively teach doctrinal truths. His hymns can be divided into two classes: those that conveyed the riches of Gospel truth, and those that spoke of the return of Christ and the coming heavenly glory. Dr. Handley Moule, the Bishop of Durham, once remarked:

“In Bonar’s hymns, the massive theology of the Reformation, say rather of St. Paul and of St. John, breaks into deep and tender melody, a crystal river from the rock. The glory of the Son of God, His finished work, His never-finished working, the power of His promised Spirit upon the heart of man, to convict, to convert, to train, to sanctify; the awe of guilt and judgment, the wonder of the blood of the Lamb, the sublime freedom of justifying grace, the walk with God through duty and suffering, the victory over death, the unutterable brightness of the promise of the second coming-all lives in his verse, that it may live in the worshipper’s soul as he sings, making the majestic doctrines embrace us, as it were, with a power full of beauty unified with truth.”

Dr. Bonar wrote well over 600 hymns, yet they were not used for public worship on the Sabbath. Theodore Cuyler recalled:

“The first time I ever saw Dr. Horatius Bonar was in May, 1872, when I was attending the Free Church General Assembly of Scotland as a delegate from the Presbyterian Church in the United States…I was glad to be introduced to him, for I was an enthusiastic admirer of his hymns…Although Horatius had won his world-wide fame as a composer of hymns, he was, at that time, stoutly opposed to the use of anything but the old Scotch version of the Psalms in church worship. During my address to the Assembly I said: ‘We Presbyterians in America sing the good old psalms of David.’ At this point Dr. Bonar led in a round of applause, and then I continued: ‘We also sing the Gospel of Jesus Christ as versified by Watts, Wesley, Cowper, Toplady and your own Horatius Bonar.‘ There was a burst of laughter, and then I rather mischievously added: ‘My own people have the privilege, not accorded to my brother’s congregation, of singing his magnificent hymns.’ By this time the whole house came down in a perfect roar, and the confused blush on Bonar’s face puzzled us—whether it was on account of the compliment, or on account of his own inconsistency. However, before his death he consented to have his own congregation sing his own hymns, although it is said that two pragmatical elders rose and strode indignantly down the aisle of the church.”

Bonar was also cognitive of the possible dangers associated with the use of hymns in worship:

“One is often inclined to ask how far some of these exulting hymns may be the utterance of excitement or sentimentalism…hymns are often the channels through which much unreality is given vent to in ‘religious life.’ Song, like music, is often deceitful, malting people unwittingly believe themselves to be what they are not. The amount of superficial similarity which has, in all ages, been introduced into and fostered in the Church by music, is incalculable. High-wrought feeling produced by it in conjunction with song, has in many a case misled both the singer and the listener into a belief that their heart was beating truly and nobly towards Christ, when all the goodness was like the morning cloud and early dew.”

The Signal, a magazine of the Free Church, publicly rebuked Bonar for his role in introducing hymns into the worship of their presbytery as he entered into the last years of his ministry. This was not the only controversy in which Dr. Bonar found himself. In 1843 he was one of the many supporters of Thomas Chalmers during the Disruption in the Church of Scotland. The abuses of patronage in the calling of ministers caused many to break away and form the Free Church of Scotland. The cause of the separation was grounded in the demand of the laity for a voice in the process of appointing ministers in opposition to the heritors whose selections went unimpeded. 474 ministers left to form the Free Church which Dr. Bonar was to remain in for more than forty years. However, the biggest public disputation that engaged Dr. Bonar was his support for the crusades of D. L. Moody in opposition to Dr. John Kennedy of Dingwall. In a series of public tracts, the two Scottish Presbyterians debated the orthodoxy of the American’s preaching and his “hyper-evangelistic” methods, with Bonar defending Moody from the charges of Kennedy.

Horatius Bonar was unable to avoid the trials and afflictions of life. He and his wife, Jane Lundie, suffered greatly when five of their children died early in life. In a moment of deep sorrow, a broken Horatius wrote, “Spare not the stroke; do with me as thou wilt; let there be naught unfinished, broken or marred; complete thy purpose that we may become thy perfect image.” Years later, when his son-in-law was taken early in life, Bonar’s daughter and five children came back to live with him and he was able to joyously write to a friend, “God took five children from me some years ago, and He has given me another five to bring up for Him in my old age.”

Through the tribulations he endured, Bonar was sustained by the sovereign hand of God working through his life and in his ministry. Horatius Bonar lived to the glory of God and the service of others, with little concern for how his own life would be remembered. It is my prayer that this CD will help to paint a clearer picture of this humble servant, while at the same time, showing us the beauty and glory of the One he served.